Letters in Greek epigraphic landscape

a talk draft for a workshop at Universiteit Gent

Introduction

Goedemorgen ! It’s my great pleasure to come back to Gent and also to participate in this great workshop, meet some old friends and talk about late antiquity. I thank Lieve, Marijke and Matthijs for the organisation and it’s so nice to meet you all, especially after the tough COVID time which we all went through. My talk today is a preliminary attempt to bring some methods from earlier periods and different areas to late antique epigraphy, especially Greek epigraphy. At the same time, I hope to see what a longue durée perspective on late-antique public documents can help us understand civic mechanism in Greek cities, especially larger cities in developing a landscape of inscriptions. My talk will be in three parts: first, a brief overview of the concept »Epigraphic landscape«; second, a thematic analysis on letters as a genre in epigraphic landscape; last part is about the exemplary case Ephesos.

Epigraphic Landscape

Many Hellenistic and Roman cities in the Hellenophone were covered with a textile full of inscriptions.

While epigraphic practice declined to a certain extent starting from the third century onwards, the presence of inscriptions (old and new) are still everywhere in late antique cities, even though new public texts were mostly found in large metropoleis.

It is against this background that epigraphers in the last decades talked more, in an archaeological glance, on the concept of epigraphic landscape.

Studies on the epigraphic landscape focus much on cities with a rich monumental and epigraphic presence: Athens, many well-excavated cities in the Latinophone west, Rome, and my dissertation on Hellenistic Delphi. Although archaeological evidence is less well preserved than earlier times, partly because of the frequent reuse of monumental and architectural blocks, in cities like Ephesos and Corinth ans cities in n africa it is still possible to read stones in landscape. Such studies take a diachronic view of inscribing practice and examine how viewers in their own times could view, understand, and interact with inscribed artefacts (walls, steles, etc.) within its environments. And reuse or continuity of inscribing play clearly a role in this diachronic development of epigraphic practice.

It is important to ask the question how viewers saw inscribed documents, both those inscribed in their time and in earlier times, as part of the city landscape. Also, we may wonder, when a new text was inscribed somewhere in a city, how did the landscape change or if it changed. To answer this question, we need to identify both the nature of the inscription-bearers (Schriftträger) and the view in a given time, in our case, late antiquity, in order to give proper interpretations. It is also crucial to understand inscriptions in types, and see how different types of texts were displayed and engaged with: my studies on manumission acts and honorific landscape in Hellenistic Delphi as an example, and today I’m talking about administrative letters.

Administrative letters as a type

Speaking of administrative letters, I guess we have already been challenged or been inspired by Corcocan and Grünbart on their definitions and scales.

In the Hellenistic periods it has been a long tradition to study ‘Royal Correspondences’, and these letters were commonly found with nice archaeological landscape records, enabling us to further explore the visual context of them.

A continuity of this practice cannot be verified for the period we are concerning today, Late Antiquity, as most of the sources we have are in ‘fragmentary nature’ or we are ‘lack of knowledge about their original location’ (in Corcoran’s words).

There are some basic info we still need to get us on the same page.

While in the Hellenistic Royal Correspondences collections, Greece mainland and Asia Minor divide a share of 4/6, in late antiquity the percentage is very unbalanced.

In the 132 entries we collect in the East from Diocletian to Markianos,

The largely unproportional geodistribution of sources resulted in the lack of epigraphic dossiers in multiple cities:

apart from the reinscribed dossier in Aphrodisias and the letters in Mylasa, most dossiers in the late-antique cities are chained texts rather than individual texts inscribed on an artefact, be it stele or temple wall. \

This leads to the big question on all kinds of administrative inscriptions: are inscribed letters to be read in their times or later times? WHile administrative letters have practical roles, the practice of inscribing them brought them into the field of rulership or »Herrschaftsschrifttum«. This was already much of the case in the Hellenistic times and more in the Principate, but it came to a peak in late-antique inscribed artefacts. We don’t find any ‘publication clause’ as did in earlier letter inscriptions, some of the edicts that ruled how to display texts are about who paid for inscribing. In this sense, inscribing by itself ceased to become a self-evident element for administrative letters, and epigraphic presence of an administrative letter which could have just been left in the city archive shows more univocal and unidirectional power, even if the letter(s) consist(s) of a corresponding sequence of letters.

Denis Feissel and Simon Corcoran have discussed much on the publication process and rendered the authority to make decision of publication to the high power, while the petitioners are responsible for their display.

In Mylasa, long after the decline of the imperial cult, the area of the temple of Augustus and Roma was still active thanks to the very recent archaeological evidence. The long podium wall of the imperial temple enables the local authority to fulfill the request by the praetorian prefect (I.Mylasa 613) to inscribe the letters of Theodosius II and his comes sacrarum largitionum in 427 CE in every Carian city. It was already since Hekatomid dynasty, so earlier than third century BCE that Carians have the tradition to inscribe administrative documents on the wall of temples. And this is a local practice as people in the hellenophone world don’t do that everywhere, especially in Greece mainland. Here, the inscription was written in one column that takes 4,5 metres long on the wall, something Hellenistic and Roman practice don’t really see. A visitor will easily see the large dedicatory text on the architrave of the temple for Augustus and Roma goddess in Greek, but when walking alongside the temple back and forth, he will have to take care of the crazily long imperial rescript if he wants to read them, a bit lower than his eye level

Similarly, Aphrodisias’ so-called ‘Archival wall’ was also understood in a way that not only local citizens but visitors to the performance will have to go past. A current visitor with nice camera will be easily able to take perfect photos with readable texts, as the later Christian readers took pains to find all the words for Aphrodite and sometimes, Augustus and erase them during the turmoil between Christians and pagans.

(An astonishing parallel was found on the other end of the Eurasia when a Chinese imperial rescript in 711 CE certifying the privilege of a Taoist temple ruled that a bronze bell be casted and the inscription was put in the bell with unreadable scripts made by the emperor. By ringing the bell as part of the ritual, the priests are literally hitting on the imperial rescript while reassuring the power of this inscribed artefact. And its presence on the bell itself brought the Herrschaft.)

Speaking of inscribed artefacts having power, it is also interesting to notice how people living in the fourth to the sixth century coped with letters already there before them. Reinterpretation of old inscribed administrative documents influenced the reusing process of temples and constructions in the late-antique period. Many of the small cities in the late antique period did not have further expansion and those old letters are thus simply ignored. We therefore luckily have many Hellenistic and early Roman letters in Thessaly, in Cilicia, and in Priene where late-antique buildings didn’t use old materials. Sometimes the stones were still taken elsewhere for reuse, but this is merely about its material value of being stone. There seems to have been a certain valid period when a certain imperial inscription can be taken up for reuse, but this needs further studies if it’s possible at all. On the right we have IK Eph. 41, a letter of Constance II to proconsul of Asia in around 351, which was found in the pavement of Embolos persumably either after the restoration of the city mentioned in the Eutropius letter by Valens in 371, or the large restoration of the city in the fifth century according to material evidence. In Thessaloniki, both the imperial rescript for Saint Demetrios and the prefect’s order were integrated into the north wall of the church, at least one hundred years later than they were inscribed. We have mentioned the practice of erasure, not only as part of damnatio memoriae, but also the continuous inscribing, as the inscription with Julian’s name erased in Aphrodisias will later receive the name of Valens on top of the erasure space! There are cases where old letters were preserved in late antiquity, though apart from the practice in Ankyra namely the res gestae of Augustus, I can’t see if I can come up with a good argumentation flow to identify a case for preservation. And also, as were the case in late Hellenistic times, cities also re-inscribe texts that they received logn time ago in a new circumstance for new reason: Aphrodisias’ archival wall was a comparable case to Attalos’ dossier in Panormos, both a century later than the original the text dossier was inscribed in a meaningful layout for a new reason. What I think it needs further thinking is to take the perspective of reading and do an archaeology for it. Whether our sources are enough is another question.

Not only were the texts read but more importantly, monuments were read as well by new people. and we are able to infer how they read monuments through how they put new texts on old monuments. This practice, which I call »Weiterbeschriftung« and perhaps »continue-inscribing« (in english? please make new suggestions!) is a crucial part both for my talk today and my dissertation in the Hellenistic Delphi. It uses the affordable space of an already existing monument, inscribed or uninscribed alike. In the dossier of scribo in Hadrianopolis in Honoriade, the new, sixth century scribe John has his very plainly administrative letters warning the bandit local elites onto an honorific statue for Commodus, which stood on a wide road in the archaeological context. We have already seen the Orcistos example in Simon Corcoran’s talk, where the front side of the pillar base was the beginning of the text and then the right, the left at the end. Here in Hadrianopolis, you have to walk around the base line by line as it was inscribed continuously from the right face to the left face, thinking about Mylasa! And to this I need help from papyrologists :) Another intriguing though uncommon practice is found in Sardeis, where a late antique governor’s edict was inscribed directly on a non-erased letter preamble from Septimius Severus. As far as I know only one case in early third century Delphi, the Siphnian Treasury where an administrative letter from the civic authority was inscribed palimpsestically on an earlier honorific decree, but please inform me if you know more cases. Here, the IMP CAES was left out and not covered, and Harriet Flower’s argument that the imperial titulars carry the authority may stand here. In Justinianopolis namely Didyma, we encounter a case where an uninscribed block was taken as inscription-bearer for the famous dossier recording the transmission of message. The block from the second century CE was originally a wide orthostate, but when in the sixth century the stonecutter took a 90° rotation and use its width as height for embedding the long dossier (Feissel, Chiron 2004). This practice we call Weiterbeschriftung but not continuous-inscribing though. And the last example on this slide, this Athenian stele recording the Caesariani dossier, was on a typical Athenian material for important administrative documents in the very early times, but here the surface was not polished first, and thus out of the epigraphic landscape in Athenian administrative documents. It is possible, I guess, that the stone itself was also reused from somewhere else as Athenians ceased to inscribe documents on such kind of stele shapes in the middle of the Principate, (but I have to verify this when I travel to Athens this November…)

A Zwischenfazit: the artefacts bearing inscribed administrative letters in late antiquity were standing between the practicality of their material and the power or authority granted to them. The reading and, depending on reading, the reusage of these artefacts were also standing between a pure (practical) materialism and a strong (intentional or even ideological) capture as spolia. While we don’t always have the ideal Standort Fundort patterns for these late-antique letter inscriptions, to study how they were read makes us to better understand both how imperial power was perceived and how ‘unsacred’ their artefacts were.

(You may have noticed that I avoid talking about Ephesos much till now, as it’s the third part because it has richest sources both in the practice of reuse and in the practice of inscribing thanks to the archaeological documentations. And this is certainly a continuation of Feissel’s 1999 article but focussing more on the practice of later usage. Whether Ephesos shall be an exception, or we can learn from Ephesos some larger mechanisms, will be a question for us all. ) Now, let the fragments talk in Ephesos.

Ephesos. cumulative texts in a changing landscape

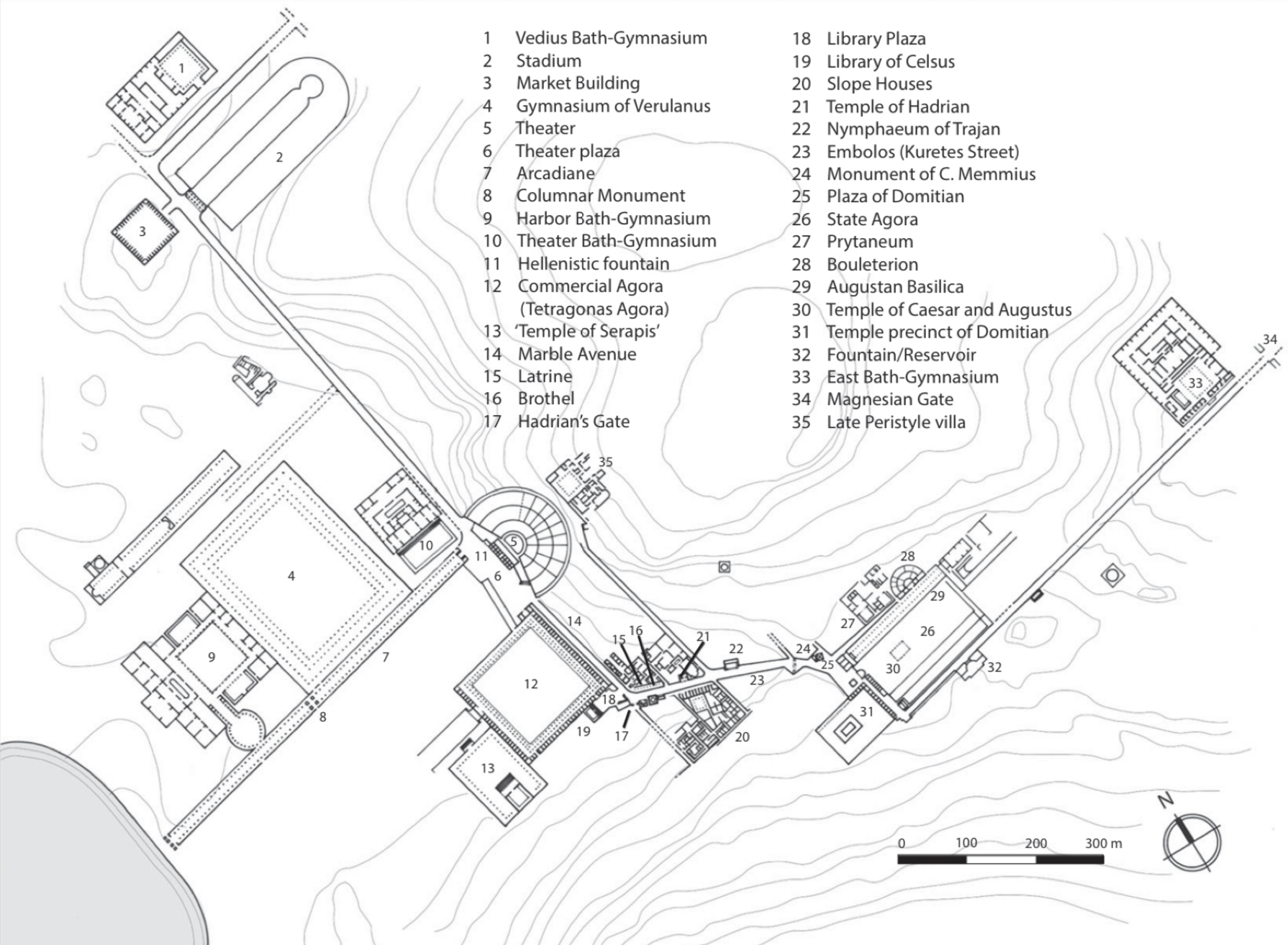

Thanks both to its metropolitan status in Provincia Asiae and to the long and detailed excavations, Ephesos was an unescapable case on any serious discussion about public epigraphy in the late antique East, just like Delphi in the Hellenistic times.

Inscribed administrative letters in Ephesos are found in many places in the city, already in the Hellenistic Period; and they were reused in different earlier times: one letter from Attalos II king of Pergamon who appointed a teacher from Ephesos for his son, later Attalos III, was inscribed on a wide block which serves perfectly as a pillar base or top. The block was then reused in a pillar from the inner hall of the Agora. Statues with Ptolemais, Attalos, and Antiochos of Commagene were taken, normally from the Agora, to the Domitian temple, to the harbour, and to private houses in the second century (the date according to archaeologists focussing on Embolos). And the practice of reuse, especially in High Empire and sometimes in Late Antiquity, was attested for around half of the Hellenistic inscriptions in Ephesos (not many though) and almost every case not in the Artemision. A Roman Senatus consultum was found in Artemision, and may have escaped from reuse as it was far from the city.

In the high empire, emperors and governors continue to write letters and they make much on steles and sometimes also on slabs for buildings, mostly on the Embolos and in the Theatre. And reuse or de-re-localisation appear in short and long terms: fragments for IEph 19b was found at the Magnesian Gate but the bulk of the text in the theatre, as an example. The Caesariani dossier copy in Ephesos have four fragments, two from the west and south pillars of the Agora, one in the Hanghaus II where we also find a statue for Ptolemais II and Arsinoe, and the last from the theatre. The practice that reusing letter blocks in fragmentary nature was done clearly in late-antique times, together with other kinds of inscriptions told us a sad story that, for those later building projects, inscribed imperial letters were not that important, though those letters themselves, we don’t know.

One of the best preserved cases with its landscape was found at the Octagon, a monument built in the Early Empire with possible Hellenistic basis and material (a new study said in the Augustan Period based on stratigraphy, I’m not 100% following but okay, definitely Early Empire but not Hadrianic, as earlier scholars argue). In front of the Octagon which was designed for a underground grave, there were high slabs or socles to cover the entrance of the grave house: by cover I mean the passage between the slabs and the entrance was thin. And it’s clear those slabs only became inscription-bearers in late antiquity when two rescripts from Valens, in different periods for two different proconsuls, were inscribed together on six socles here, in column! The first, in 371 to Eutropius on the civic revenues, was purely in Latin, and the second to Festus a later proconsul but in five years about the contests in the provincia Asiae, was in Latin original and a local Greek translation. Two texts were written in very similar hands (and I beg you to believe me or to believe in André Chastagnol). While both rescripts are famous to many of you, it strikes me why, while they were inscribed together and perhaps from the same commission, only one has a Greek translation and the other in Latin? A possible interpretation, and I don’t agree with Chastagnol here, is that the local Greek trans. was for visitors, especially those elites from other cities in provincia to alarm them, don’t run your own contest but stay in the provincial games. It may be due to this that they found the slabs in front of the Octagon, very prominent in location and not inscribed. So we meet the phenomenon of Weiterbeschriftung, the language problem, and the local landscape of inscriptions and then I ask the question who was in charge of this writing? I would give more weight to the Ephesian community than to Festus here.

The last slide is about church documents. We know there are two main churches in Ephesos in the sixth century: one is St. John, for which Justinian wrote a honorific letter that was found on the Agora door! Also about St. John Justinian showed his preference over Smyrna’s Polycarp in a letter IK I 45, but the text was reused in a pavement of the Domitian Piaza. This may have to do with the fact that St. John was beyond the city area and display of this honour was for the city rather than for the church itself. The other is famous for holding the two Ephesian council and the Austrians sometimes call it Konzilskirche but it’s the city’s cathedral St. Mary. We find from here six letters in Feissel’s catalogue, all about ecclesiastical affairs, and perhaps from a single dossier owned by bishop Hypatios. We have here a Justinian’s fragmentary rescript, another letter which we wait for Feissel’s edition, an arbitrary letter between St. Mary and St. John, and very interestingly, a pastoral letter by himself to the city of Ephesos. These texts were found everywhere in St. Mary as a living church for long time, but must have been in a certain place before they were reused in tombs within the church or in the narthex, or in the baptistery, or in the front courtyard. This further blurrs the division of epigraphic practice between ‘ecclesiastical’ and ‘secular’ documents, as this dossier, from the promulgation to the collection and the reuse, are just so common as we see in other areas in Ephesos. It does occupies a special landscape in the city, but occupies in a way as other Ephesian texts did!

Concluding Remarks

So yes, and I think it’s still an ongoing process before I finalise a written version of this paper. And if you find something interesting in my talk, I’ll be very glad.

Thank you for your attention, and I’m looking forward to your questions, vos remarques, und Ihre Anmerkungen.

Appendix

| lemma | location | material description | location | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PPRET 23 | Delphi | double-sided slab | unknown | |

| SEG 32.849 | Chalkis | slab | unknown | |

| SEG 11.464 | Sparta | column | reused from IIp building | |

| CIL 03, 00568 | Amphissa | tafel | reused in church Metamorphoses Soter, from Gymnasium | |

| IG 04, 00364 | Corinth | |||

| Feissel Recueil 81 | Thessaloniki | church block | church (later reused within church) | |

| Feissel Recueil 85 | Thessaloniki | marble block | reused in city wall | |

| BCH 91, 588 n35 | Thasos | fragment | unknown | |

| BCH 108, 158 n8 | Abydos | |||

| IK Eph. 1.38+4.1371 | Ephesos | |||

| IK Eph. 1.41 | Ephesos | panel stele | reused in the pavement (on Embolos) | |

| IK Eph. 1.42-43 | Ephesos | orthostate of a building | octagon (reuse from Ip building) | |

| IK Eph. 1.44 | Ephesos | |||

| IK Eph. 2.224 | Ephesos | |||

| IK Eph. 4.1329+41 | Ephesos |

| IK Eph. 4.1345 | Ephesos | ||

| AE 2020, 1215 | Ephesos | base of statue in marble | Church of Sainte-Marie |

| I.Mylasa 611–2 | Mylasa | ||

| I.Mylasa 613 | Mylasa | ||

| AE 2000, 01370a | Amorgos | stele | city gate |

| AE 2000, 01370b | Amorgos | stele | city gate |

| IG XII 4,1,273 | Kos | plate | unknown |

| Chiron 34, 2004 | Didyma | stele | reused in the pavement (sacred way) but itself reused first |

Appendix: Materiality and Landscape of selected imperial letters in Late Antiquity

- Delphi, 341–346 (unedited). Found on two fragments of slab(s) in marble, originally in the city archive.

- Chalkis, 359 (SEG 32-849). Found on a thick block in marble, reused in a wall nearby the central agora, originally in the central section of the city.

- Sparta, 359 (SEG 11-464). Fragment in the theatre; reused from a building in the second century.

- Amphissa, fourth century (IG IX2 751). reused in church Metamorphoses Soter, originally from Gymnasium.

- Corinth, second half of the fourth century (IG IV2 3, 1814). a marble base, found into a modern structure in Korakou area. [5bis. Corinth, 401/2 (IG IV2 3, 1242). White marble fragment probably reworked for this inscription, found in the Amphitheatre.]

- Gortyna, fifth century (I.Cret. IV 507). Marble fragment, found near the Hagios Deka.

- Thessaloniki, 533–565 (IG X 2, 1, 23). Marble stele, found by the oikonomos at St. Demetrius church, reused in the north wall.

- Thessaloniki, fifth or sixth century (IG X 2, 1, 22). Marble stele with tabula ansata. Found reused in the eastern rampart of the city, original spot unknown. [9bis. Thessaloniki, 688 (IG X 2, 1, 24). Marble stele, found on the floor of St. Demetrius, perhaps paved in later times.]

- Thasos, fifth century (BCH 91, 1967, n.35). Fragment of a marble stele found reused in a modern wall between the ancient agora and the port, original spot unknown.

- Amorgos, 362 (AE 2000, 1370). Two marble steles found at the port of Minoa on Amorgos, in Latin.

- Kos, fourth century (IG XII 4, 272). Fragment of a marble slab found reused in the area near casa Romana, perhaps in the fifth or sixth century. Original spot unknown.

- Kos, 371 (IG XII 4, 273), two fragments of a marble slab found near the church Hepta Vimata, in the cemetery Hagios Ioannis to the south of the city of Kos.

- Abydos, 550–51 (BCH 108, 1984, 581–98), a wide marble stele found on the site of ancient Abydos. The end of the text as well as the notitia was preserved. 45bis. Annaia, 386/450 (EA 53, 2020, 173–77). A stone slab bearing an erased text in tabula ansata, later reused in a Byzantine church.

- Mylasa, 427/9 (I.Mylasa 611–12). Inscribed on the podium of the temple of Augustus and Roma, one below the other.

- Mylasa, 480 (I.Mylasa 613). Weiterbeschriftung following 46, with long lines along the podium wall at eye level.

- Kırkpınar (Lagbe), 1 June 527 (CIL III 13640), about the Church of St. John (near Kibyra), around 87 kilometres to the east of the church. A squared block on a round base, Latin texts inscribed on three faces, on the fourth face is a Greek translation. Found in a space with no clear context.

- Didyma/Justinianoupolis, 527–533 (I.Didyma 596). A heading gable of an edict of Justinian, inscribed in the pediment-shaped triangle of the gable, below a cross; decoration with peacoats and guineafowl (?). Found to the right under the Byzantine stairs in the pronaos of the converted temple of Apollo.

- Didyma/Justinianoupolis, 533 (SEG 54-1178). Tall and thick white marble perpend found reused in an apsidal masonry by the SE sector of the Sacred Way.

- Miletos, 539–542 (Milet VI 3, 1576). Three fragments, two found near the “Lions’ Bay”, main port of Miletos.

- Aphrodisias, late sixth/early seventh century (I.Aphrodisias 15.363). Inscribed on an existing monument “along the way” in Aphrodisias, stone lost.

- Sardis, after 539 (I.Sardis I, 19). Marble slab found in the south face of the bastion of the acropolis wall.

- Sardis, around 535 (I.Sardis I, 20). Marble slab found in a field expanded in Roman period. Inscribed over a partly eradicated dedication to Septimius Severus (I.Sardis I, 71), and to the left side, a contract with the association of building labourers (SEG 52-1177, 459 CE).

- Orkistos, 324–6 and 331 (AE 1999, 1577). Marble pillar. The letters inscribed in 324–6 occupied the space on the front moulding, the shaft, the bottom moulding and continued the engraving on the left and right faces. Another letter in 331 occupied the still available space on the right face.

- Antioch of Pisidia, fourth century (I. Antioche Pisidie Ramsay 203). No clear description on material from the records.

- Ikonion, fifth century (TAM Ergänz. 11, Beiträge zu den griechischen Inschriften Lykaoniens, n.49). Fragment of a thick marble block, (modern time?) reused in a house. 59bis. Limyra, between 384–7 and c. 450 (SEG 65-1470). Found on a monumental equestrian statue base with four orthostates (one lost) on the southwestern corner of the southern portico along the “Säulenstraße”. On the south face engraved an honorific text for Flavius Theodosius on an erased text; on the west face inscribed the edict.

- Perge, 344–351 (unedited). S. Şahin noted that the slab bearing an honorific text for Flavius Philippus was located upon two inner pillars of the Hadrian Gate, on which the unedited letter was inscribed.

- Perge, 491–518 (SEG 65-1408). Three thin marble slabs, perhaps originally employed in parapets and reused as inscription-bearers. Most of the fragments found by the northern junction of the colonnaded street and the street extending between the east and west city gates.

- Kasai, 478 (SEG 66-1716), “la grande inscription”, on the exterior wall of an apse of the “inscribed church”, both on the flat and on the curved walls.

- Hadrianoupolis, sixth century (SEG 35-1360). Marble base with mouldings above and below originally for a statue of Commodus; the three remaining faces bore a letter from the imperial scribe, with each line inscribed along the three faces.

- Amastris, 527–533 (SEG 46-1620). Two fragments of reddish stone found on a hill near the village, findspot not important.

- Germia, 532? (SEG 36-1180). Two fragments of a white marble tablet, with difference in letter size, reused as a cover of a tomb.

- Korykos, 507–510 (MAMA III 197). Inscribed on two altars in marble, found reused as the doorpost of the East Gate of the city fortress.

- Seleukeia Pieria, sixth century (SEG 35-1523). Four fragments of a marble slab, no original findspot.

- Beroia, 565–578 (IGLS II 262). Three fragments of a pillar in basalt. No clear findspot.

- Apameia, fifth century (IGLS IV 1385). Fragment of a marble stele, no clear findspot.

- Maʾṣūb near El-Bassa, rural area of Tyre, sixth century (SEG 8-18). Fragment of a marble stele, with ornaments of five busts on top of the text for the oratory of Saint Zachariah. 78bis. Kafra/Naffakhiyé near Tyre, sixth century (I.Mus.Beyrouth 329). Eight fragments of a stele in limestone. A rescript of asylia for an oratory (?) like No.48? 78tris. Tyre (?), early Byzantine period (I.Mus.Beyrouth 311).

- Emesa, fifth or sixth century (I.Mus.Beyrouth 398). Fragment of a marble stele, probably in the living area of Homs, no clear original spot. 79bis. Hama (near Emesa), fourth century (or earlier?) (I.Mus.Beyrouth 385 = SEG 66-1898). Two fragments at the right end of a marble stele,

- Palmyra, fifth century (?) (IGLS 17.1, 359). Fragment at the bottom of a marble stele. No certain findspot.

- Jerusalem, 492 or 507 (CIIP I, 2, 784). Local limestone block, (perhaps in modern times) reused on the southern side of the Church of Holy Sepulchre. Originally around 8–9 metres long.

- Jerusalem, 533–565 (CIIP I, 2, 785). Reused in the Cosmatesque pavement in Apse 16 of the Rotunda.

- Jerusalem, Mauritius? (CIIP IV, 2, 3431). Limestone slab, perhaps found near Bethlehem, near an aqueduct.

- Beersheba, 536 or shortly thereafter (SEG 54-1643), seven fragments of a large marble slab, having a clear layout for the tax paying record. No findspot located.

- Qaṣr al-Ḥallābāt, 492 (Arce/). More than 160 fragments of basalt blocks found mostly in an Ghassanid complex, perhaps originally from the West Church or the perimeter wall of pretorium of Umm el-Jimal (Hauran, Classical Aur